Casablanca – Film Review.

“I really enjoyed the chat before Casablanca by the young gentleman. It really helped put the film in context”

We were honoured to have local Borough Councillor (and self-confessed film geek) Andrew Schrader to introduce our showing of Casablanca on the 18th February. This was the first time we had provided some background to a film and were unsure of how it would be received. We underestimated our audience, of course. The feedback we received was very positive and so no doubt we’ll be doing this again. Our thanks to Andrew – and if you want to find out more about the background to Casablanca, read on!

Casablanca, by Andrew Schrader.

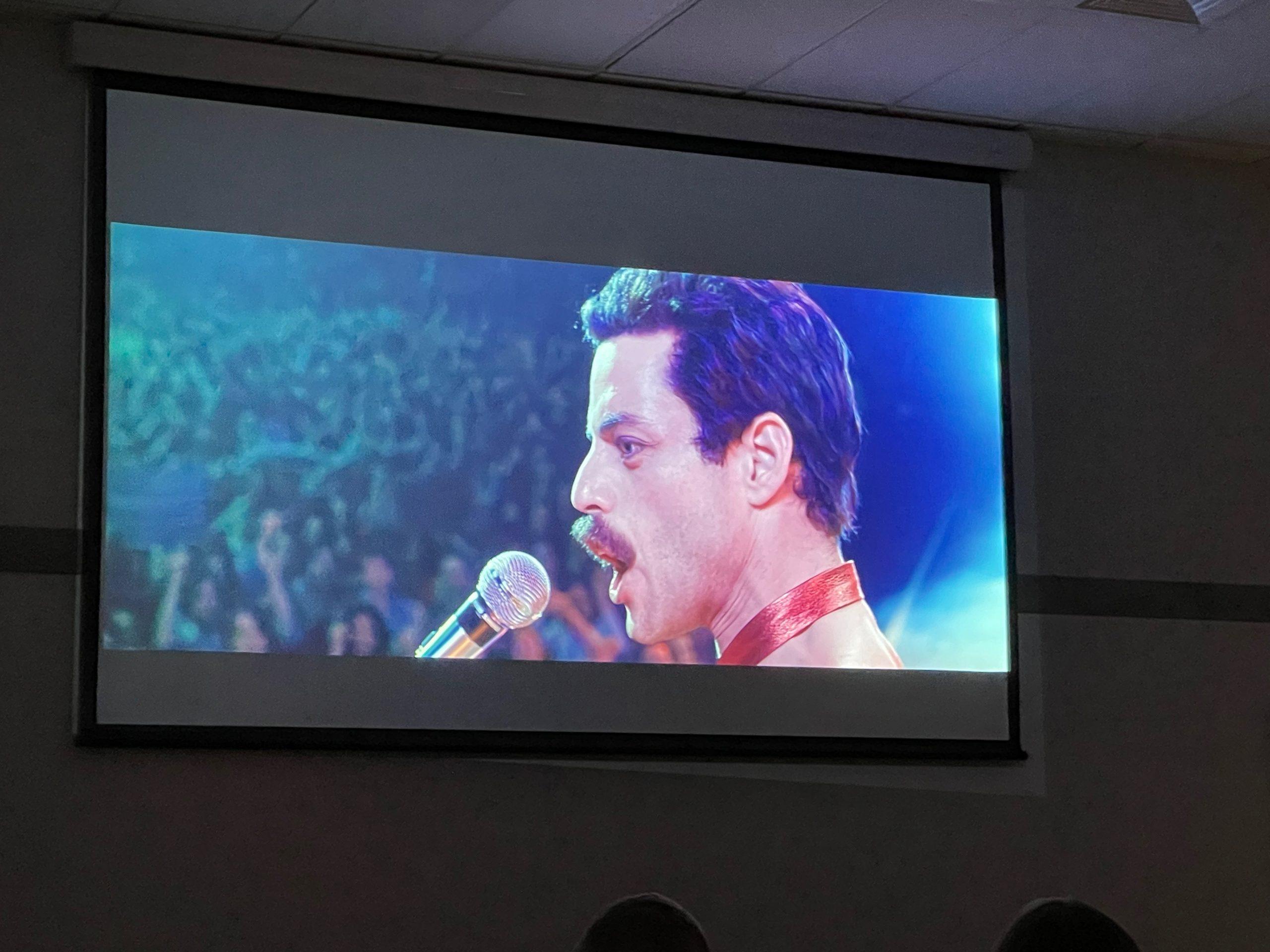

If you search any list of the Top Ten Greatest Films of All Time, Casablanca will feature in most of them. It is widely regarded as one of the best films ever made. Essentially, it is the tale of a love triangle between two men vying for the same woman’s love against the backdrop of World War II political espionage in the North African town of Casablanca, then controlled by the pro-Nazi regime of Vichy France.

If you search any list of the Top Ten Greatest Films of All Time, Casablanca will feature in most of them. It is widely regarded as one of the best films ever made. Essentially, it is the tale of a love triangle between two men vying for the same woman’s love against the backdrop of World War II political espionage in the North African town of Casablanca, then controlled by the pro-Nazi regime of Vichy France.

Released by Warner Bros. studios over 70 years ago, it remains a favourite of moviegoers. What gives it such enduring popularity with audiences? It was made during the war itself – first released in late 1942 and then rushed into general release in 1943 three weeks after the Allied landing at Casablanca; when General Eisenhower’s forces were marching into the actual city (meaning Warner Bros. could capitalise on some free publicity).

The film was based on an unproduced play written by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison called Everybody Comes to Rick’s. In the summer of 1938, Burnett and his wife had travelled to Vienna shortly after the Anschluss to help Jewish relatives smuggle money out of Austria. They later visited a small town in southern France and went to a nightclub, where a black pianist played jazz for a crowd of French, Germans and refugees. Burnett returned to the US via England and, whilst in Bournemouth, started to make notes for his anti-Nazi play. In 1940, he completed the play in collaboration with Joan Alison.

They were unable to find a Broadway producer to stage the play – largely due to unease at the hints of sexual impropriety between the two central characters – and that is where the story might have ended. But a woman named Irene Diamond discovered the play during a trip to New York in 1941. She was a Hollywood talent scout for Warner Bros. and took it to the man who would eventually make the film possible – legendry Hollywood film producer Hal B. Wallis.

Wallis bought the rights for $20,000 – then a record for an unproduced play – and he, in my opinion, more than anyone else, deserves credit for making the film possible. The project was re-named Casablanca and began filming in May 1942, wrapping in August of that year at a cost of just over $1 million. Although most film shoots are usually non-linear, with the ending invariably being filmed first, Casablanca was filmed in sequence. This was because, at the time they started filming, only the first half of the script was written. The script was in the hands of twins Julius and Philip Epstein (Howard Koch was also credited, though none of his pages were actually used) and, by and large, the script was written day-by-day, so nobody on the set could be sure how the film would end. Who would use the two ‘exit visas’? Would Rick’s former lover leave with her husband or with him? The actors themselves did not know until they were on set and handed the final lines of dialogue.

Apart from a scene shot at Van Nuys Airport in Los Angeles, the film was shot entirely at Warner Bros’ Burbank studios in Hollywood, with some stock footage of Paris used for the flashback scenes. Wallis’ first choice for director was actually William Wyler (who you probably know best as the director of Ben-Hur) but he was unavailable, so Wallis turned to his close friend Michael Curtiz, a Hungarian Jewish emigre who had come to the US in the ’20s but had relatives who fled Europe during the war. Curtiz is a greatly underrated director, in my opinion, and while the quality of his work varied after the 1940s, I’d recommend Angels with Dirty Faces with James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart.

The role of Rick Blaine was an important one for Bogart, it being his first truly romantic lead. Just to confirm, it is an urban myth that future US President Ronald Reagan was initially considered for the role but Bogey did have to fight off George Raft for the part. He was cast opposite Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman as Ilsa Lund, in what became her most famous and enduring role. She beat off competition from other ’40s starlets, including Hedy Lemarr, but Wallis was determined to get her. She was on contract to David O. Selznick but Wallis secured her but lending him Olivia de Havilland in exchange. The chemistry between Bogart and Bergman was luminescant – though there were difficulties caused by the fact Bergman was a good two inches taller and legend has it that, for some scenes, Curtiz had Bogey stand on bricks or sit on cushions.

The picture assembled a truly international cast. One of the things I think gives it resonance with audiences is that it is a film about people fleeing Nazi persecution made by people who, in many cases, were actually fleeing Nazi persecution. Paul Henreid, who plays Victor Laszlo, was an Austrian aristocrat who fled just prior to the Anschluss, as did Peter Lorre, who plays Signor Ugarte. Conrad Veidt, who plays the villainous Major Strasser, was actually a refugee German actor, who fled the Nazis but was frequently cast as one in American films. S. Z. Sakall, who plays Carl the Waiter, was a Hungarian-Jew, who fled Germany in 1939 (three of his sisters later died in a concentration camp). Madeleine LeBeau and her husband Marcel Dalio, who play Rick’s girlfriend Yvonne and Emil the Croupier respectively, both fled occupied France. Helmut Dantine, who plays the roulette player, was another Austrian, who actually spent time in a concentration camp himself after the Anschluss and fled Europe after being freed. There were many, many more, both in the extended cast and the crew. Much of the emotional impact of the film has been attributed to this large quotient of European exiles and refugees. A witness to the filming of the famous “Duel of the Anthems” scene in Cafe Americain, said he saw many of the actors crying and “realised they were all real refugees”. I think this explains the quiet understanding and desperation conveyed even in the dozen or so small roles in Casablanca.

The music was written by Max Steiner, best known for Gone with the Wind, the most famous song of the film is undoubtedly As Time Goes By by Herman Hupfeld but it was actually written in 1931 and featured in the original play. After filming wrapped, Steiner wanted to write his own composition to replace it but Bergman had already cut her hair short for her next role, so could not re-film her scenes. Steiner subsequently ended up using it, along with La Marseillaise, as the motiff for his entire score. Incidentally, the character of Sam, which has since become the iconic arcetype of a smokey jazz club pianist, was played by Dooley Wilson, a drummer who had to fake playing the piano. Wallis originally considered making the character female and casting Ella Fitzgerald but decided against it.

Casablanca was a box office success, thanks to brilliant performances from Bogart and Bergman but also Claude Rains as Captain Renault (who, for my money, steals every scene he is in), neat direction by Curtiz, the engrossing story of Burnett and Alison, snappy dialogue from the Epsteins, Steiner’s brilliant score and Wallis’ vision. It was nominated for eight Oscars at the 1944 Academy Awards, winning for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay. When the award for Best Picture was announced, Wallis got up to accept only to see studio head Jack Warner bound onto the stage and members of his family blocking the aisle, so Wallis had no choice but to sit back down. He quit Warner Bros. the following month and remained furious about it forty years later. So, when enjoying this film, spare a thought for Hal B. Wallis, the man who brought it to life.